Andrea Carson received funding in 2017 from Facebook for a report on the future of newsrooms. She also has Australian Research Council funding to use big data to examine public debate and public policy decisions: DP180101711

Kate Farhall ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

RMIT University a apporté des fonds à The Conversation AU en tant que membre bienfaiteur.

La Trobe University apporte un financement en tant que membre adhérent de The Conversation AU.

Voir les partenaires de The Conversation France

During the 2019 election, a news story about the Labor Party supporting a “death tax” – which turned out to be fake – gained traction on social media.

Now, Labor is urging a post-election committee to rule on whether digital platforms like Facebook are harming Australian democracy by allowing the spread of fake news.

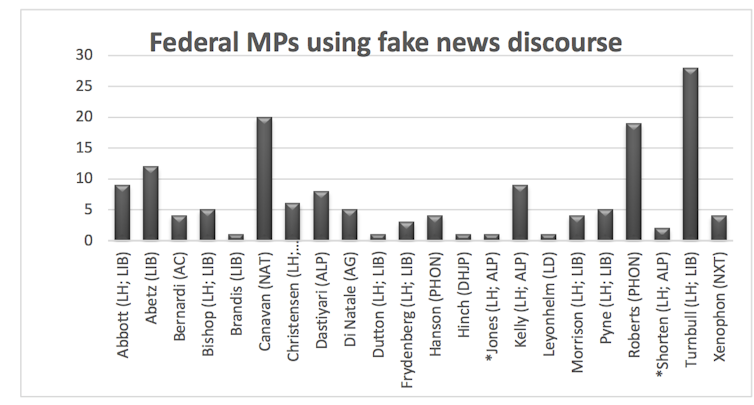

While the joint standing committee on electoral matters (JSCEM) will not report until July next year, our latest research finds that politicians are key culprits turning the term “fake news” into a weapon.

Following the election of Donald Trump as president of the United States, we investigated if Australian politicians were using the terms “fake news”, “alternative facts” and “post-truth”, as popularised by Trump, to discredit opponents.

With colleagues Scott Wright, William Lukamto and Andrew Gibbons, we investigated if elite political use of this language had spread to Australia. For six months after Trump’s victory, we searched media reports, Australian parliamentary proceedings (Hansard), and politicians’ websites, press releases, Facebook and Twitter communications.

We discovered a US contagion effect. Australian politicians had “weaponised” fake news language to attack their opponents, much in the way that Trump had when he first accused a CNN reporter of being “fake news”.

Second, we argue the media’s failure to refute fake news accusations has adverse consequences for public debate and trust in media. We recommend journalists rethink how they respond when politicians accuse them of being fake news or of spreading dis- and misinformation when its usage is untrue.

Third, academics such as Harvard’s Claire Wardle argue that to address the broader problem of information disorders on the web, we all should shun the term “fake news”. She says the phrase:

is being used globally by politicians to describe information that they don’t like, and increasingly, that’s working.

On the death tax fake news during the 2019 election, Carson’s research for a forthcoming book chapter found the spread of this false information was initiated by right-wing fringe politicians and political groups, beginning with One Nation’s Malcolm Roberts and Pauline Hanson.

One Nation misappropriated a real news story discussing inheritance tax from Channel Seven’s Sunrise program, which it then used against Labor on social media. Among the key perpetrators to give attention to this false story were the Nationals’ George Christensen and Matt Canavan. As with the findings in our study, social media users parroted this message, further spreading the false information.

While Labor is urging the JSCEM to admonish the digital platforms for allowing the false information about the “death tax” to spread, it might do well to reflect that the same digital platforms along with paid television ads enabled the campaigning success of its mischievous “Mediscare” campaign in 2016.

In a separate study, Carson with colleagues Shaun Ratcliff and Aaron Martin, found this negative campaign, while not responsible for an electoral win, did reverse a slump in Labor’s support to narrow its electoral defeat.

Perhaps the JSCEM should also consider the various ways in which our politicians employ “fake news” to the detriment of our democracy.